作者: Nikhil Buduma

出版社: O'Reilly Media

副标题: Designing Next-Generation Machine Intelligence Algorithms

出版年: 2017-6-29

页数: 304

定价: USD 43.99

装帧: Paperback

ISBN: 9781491925614

- Chapter 1. The Neural Network

- Chapter 2. Training Feed-Forward Neural Networks

- Chapter 3. Implementing Neural Networks in TensorFlow

- Installing TensorFlow

- Creating and Manipulating TensorFlow Variables

- TensorFlow Operations

- Placeholder Tensors

- Sessions in TensorFlow

- Navigating Variable Scopes and Sharing Variables

- Managing Models over the CPU and GPU

- Specifying the Logistic Regression Model in TensorFlow

- Logging and Training the Logistic Regression Model

- Leveraging TensorBoard to Visualize Computation Graphs and Learning

- Building a Multilayer Model for MNIST in TensorFlow

- Chapter 4. Beyond Gradient Descent

- Local Minima in the Error Surfaces of Deep Networks

- How Pesky Are Spurious Local Minima in Deep Networks?

- Flat Regions in the Error Surface

- When the Gradient Points in the Wrong Direction

- Momentum-Based Optimization

- A Brief View of Second-Order Methods

- Learning Rate Adaptation

- Optimization Algorithms Experiment

- Chapter 5. Convolutional Neural Networks

- Vanilla Deep Neural Networks Don’t Scale

- Filters and Feature Maps

- Full Description of the Convolutional Layer

- Max Pooling

- Full Architectural Description of Convolution Networks

- Closing the Loop on MNIST with Convolutional Networks

- Building a Convolutional Network for CIFAR-10

- Visualizing Learning in Convolutional Networks

- Leveraging Convolutional Filters to Replicate Artistic Styles

- Chapter 6. Embedding and Representation Learning

- Chapter 7. Models for Sequence Analysis

- Analyzing Variable-Length Inputs

- Tackling seq2seq with Neural N-Grams

- Implementing a Part-of-Speech Tagger

- Dependency Parsing and SyntaxNet

- Beam Search and Global Normalization

- A Case for Stateful Deep Learning Models

- Recurrent Neural Networks

- The Challenges with Vanishing Gradients

- Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Units

- Implementing a Sentiment Analysis Model

- Solving seq2seq Tasks with Recurrent Neural Networks

- Augmenting Recurrent Networks with Attention

- Chapter 8. Memory Augmented Neural Networks

- Chapter 9. Deep Reinforcement Learning

Chapter 1. The Neural Network

The Neuron

Figure 1-6. A functional description of a biological neuron’s structure

The neuron receives its inputs along antennae-like structures called dendrites. Each of these incoming connections is dynamically strengthened or weakened based on how often it is used (this is how we learn new concepts!), and it’s the strength of each connection that determines the contribution of the input to the neuron’s output. After being weighted by the strength of their respective connections, the inputs are summed together in the cell body. This sum is then transformed into a new signal that’s propagated along the cell’s axon and sent off to other neurons.

Figure 1-7. Schematic for a neuron in an artificial neural net

Just as in biological neurons, our artificial neuron takes in some number of inputs, $x_1, x_2, \cdots, x_n$, each of which is multiplied by a specific weight, $w_1, w_2, \cdots, w_n$. These weighted inputs are, as before, summed together to produce the logit of the neuron, $z=\sum_{i=0}^n w_ix_i$. In many cases, the logit also includes a bias, which is a constant (not shown in the figure). The logit is then passed through a function to produce the output . This output can be transmitted to other neurons.

Let’s reformulate the inputs as a vector $x = [x_1,x_2,\cdots,x_n]$ and the weights of the neuron as $w = [w_1,w_2,\cdots,w_n]$. Then we can re-express the output of the neuron as $y=f(x \cdot w + b)$, where b is the bias term.

Feed-Forward Neural Networks

Figure 1-9. A simple example of a feed-forward neural network with three layers (input, one hidden, and output) and three neurons per layer

The bottom layer of the network pulls in the input data. The top layer of neurons (output nodes) computes our final answer. The middle layer(s) of neurons are called the hidden layers, and we let $w_{i,j}^{(k)}$ be the weight of the connection between the $i^{th}$ neuron in the $k^{th}$ layer with the $j^{th}$ neuron in the ${k+1}^{st}$ layer. These weights constitute our parameter vector, $\theta$, our ability to solve problems with neural networks depends on finding the optimal values to plug into $\theta$.

We note that in this example, connections only traverse from a lower layer to a higher layer. There are no connections between neurons in the same layer, and there are no connections that transmit data from a higher layer to a lower layer. These neural networks are called feed-forward networks.

Linear Neurons

Figure 1-10. An example of a linear neuron

Sigmoid, Tanh, and ReLU Neurons

Sigmoid

$f(z)=\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}$

Figure 1-11. The output of a sigmoid neuron as z varies

Tanh

Tanh neurons use a similar kind of S-shaped nonlinearity, but instead of ranging from 0 to 1, the output of tanh neurons range from −1 to 1.

Figure 1-12. The output of a tanh neuron as z varies

ReLU

Restricted linear unit (ReLU) neuron uses the function f(z)=max(0,z), resulting in a characteristic hockey-stick-shaped response, as shown in Figure 1-13.

Figure 1-13. The output of a ReLU neuron as z varies

Softmax Output Layers

We require the sum of all the outputs to be equal to 1. Letting $z_i$ be the logit of the $i^{th}$ softmax neuron, we can achieve this normalization by setting its output to:

$y_i=\frac{e^{z_i}}{\sum_i e^{z_j}}$

Chapter 2. Training Feed-Forward Neural Networks

The Fast-Food Problem

Figure 2-1. This is the neuron we want to train for the fast-food problem

In this case, let’s say we want to minimize the square error over all of the training examples that we encounter. More formally, if we know that $t^{(i)}$ is the true answer for the $i^{th}$ training example and $y^{(i)}$ is the value computed by the neural network, we want to minimize the value of the error function E:

$E=\frac{1}{2}\sum_i(t^{(i)}-y^{(i)})^2$

Gradient Descent

Let’s say our linear neuron only has two inputs(and thus only two weights, $w_1$ and $w_2$). Then we can imagine a three-dimensional space where the horizontal dimensions correspond to the weights $w_1$ and $w_2$, and the vertical dimension corresponds to the value of the error function E.

Figure 2-2. The quadratic error surface for a linear neuron

We can also conveniently visualize this surface as a set of elliptical contours, where the minimum error is at the center of the ellipses.

In fact, it turns out that the direction of the steepest descent is always perpendicular to the contours. This direction is expressed as a vector known as the gradient.

Suppose we randomly initialize the weights of our network so we find ourselves somewhere on the horizontal plane. By evaluating the gradient at our current position, we can find the direction of steepest descent, and we can take a step in that direction. Then we’ll find ourselves at a new position that’s closer to the minimum than we were before. We can reevaluate the direction of steepest descent by taking the gradient at this new position and taking a step in this new direction. This algorithm is known as gradient descent.

Figure 2-3. Visualizing the error surface as a set of contours

The Delta Rule and Learning Rates

Figure 2-4. Convergence is difficult when our learning rate is too large

Define the learning rate $\epsilon$, we want:

\[\Delta w_k=-\epsilon \frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k}=-\epsilon\frac{\partial}{\partial w_k}(\frac{1}{2}\sum_i(t^{(i)}-y^{(i)})^2)=\sum_i \epsilon(t^{(i)}-y^{(i)})\frac{\partial y_i}{\partial w_k}=\sum_i \epsilon x_k^{(i)}(t^{(i)}-y^{(i)})\]Gradient Descent with Sigmoidal Neurons

$z=\sum_k w_k x_k$

$y=\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}$

Taking the derivative of the logit with respect to the inputs and the weights:

$\frac{\partial z}{\partial w_k}=x_k$

$\frac{\partial z}{\partial x_k}=w_k$

The derivative of the output with respect to the logit:

$\frac{dy}{dz}=\frac{e^{-z}}{(1+e^{-z})^2}=\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}\frac{e^{-z}}{1+e^{-z}}=\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}}(1-\frac{1}{1+e^{-z}})=y(1-y)$

We then use the chain rule to get the derivative of the output with respect to each weight:

$\frac{\partial y}{\partial w_k}=\frac{dy}{dz}\frac{\partial z}{\partial w_k}=x_k y(1-y)$

Putting all of this together:

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial w_k}=\sum_i\frac{\partial E}{\partial y^{(i)}}\frac{\partial y^{(i)}}{\partial w_k}=-\sum_i x_k^{(i)} y^{(i)}(1-y^{(i)})(t^{(i)}-y^{(i)})$

Thus, the final rule for modifying the weights becomes:

$\Delta w_k=\sum_i \epsilon x_k^{(i)}y^{(i)}(1-y^{(i)})(t^{(i)}-y^{(i)})$

The Backpropagation Algorithm

Figure 2-5. Reference diagram for the derivation of the backpropagation algorithm

- y:refer to the activity of a neuron

- z:refer to the logit of the neuron

Calculate the error function derivatives at the output layer:

$E=\frac{1}{2}\sum_{j \in output}(t_j-y_j)^2 \Rightarrow \frac{\partial E}{\partial y_j}=-(t_j-y_j)$

Let’s presume we have the error derivatives for layer j. We now aim to calculate the error derivatives for the layer below it, layer i. To do so, we must accumulate information about how the output of a neuron in layer i affects the logits of every neuron in layer j. This can be done as follows, using the fact that the partial derivative of the logit with respect to the incoming output data from the layer beneath is merely the weight of the connection $w_{ij}$:

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial y_i}=\sum_j\frac{\partial E}{\partial z_j}\frac{d z_j}{d y_j}=\sum_j w_{ij}\frac{\partial E}{\partial z_j}$

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial z_j}=\frac{\partial E}{\partial y_j}\frac{d y_j}{d z_j}=y_j (1-y_j) \frac{\partial E}{\partial y_i}$

Combining these two together, we can finally express the error derivatives of layer i in terms of the error derivatives of layer j:

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial y_i}=\sum_j w_{ij}y_j(1-y_j)\frac{\partial E}{\partial y_j}$

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial w_{ij}}=\frac{\partial z_j}{\partial w_{ij}}\frac{\partial E}{\partial z_j}=y_i y_j(1-y_j)\frac{\partial E}{\partial y_j}$

Finally, we sum up the partial derivatives over all the training examples in our dataset.

$\Delta w_{ij}=-\sum_{k \in dataset} \epsilon y_i^{(k)}y_j^{(k)}(1-y_j^{(k)})\frac{\partial E^{(k)}}{\partial y_j^{(k)}}$

Stochastic and Minibatch Gradient Descent

Figure 2-6. Batch gradient descent is sensitive to saddle points, which can lead to premature convergence

SGD:

Figure 2-7. The stochastic error surface fluctuates with respect to the batch error surface, enabling saddle point avoidance

In mini-batch gradient descent, at every iteration, we compute the error surface with respect to some subset of the total dataset (instead of just a single example). This subset is called a minibatch, and in addition to the learning rate, minibatch size is another hyperparameter.

$\Delta w_{ij}=-\sum_{k \in minibatch} \epsilon y_i^{(k)}y_j^{(k)}(1-y_j^{(k)})\frac{\partial E^{(k)}}{\partial y_j^{(k)}}$

Test Sets, Validation Sets, and Overfitting

Figure 2-8. Two potential models that might describe our dataset: a linear model versus a degree 12 polynomial

Figure 2-9. Evaluating our model on new data indicates that the linear fit is a much better model than the degree 12 polynomial

Figure 2-10. A visualization of neural networks with 3, 6, and 20 neurons (in that order) in their hidden layer

Figure 2-11. A visualization of neural networks with one, two, and four hidden layers (in that order) of three neurons each

This leads to three major observations.First, the machine learning engineer is always working with a direct trade-off between overfitting and model complexity.

Second, it is very misleading to evaluate a model using the data we used to train it

Figure 2-12. We often split our data into nonoverlapping training and test sets in order to fairly evaluate our model

Third, it’s quite likely that while we’re training our data, there’s a point in time where instead of learning useful features, we start overfitting to the training set. To avoid that, we want to be able to stop the training process as soon as we start overfitting, to prevent poor generalization. To do this, we divide our training process into epochs. An epoch is a single iteration over the entire training set.

At the end of each epoch, we want to measure how well our model is generalizing. To do this, we use an additional validation set.

Figure 2-13. In deep learning we often include a validation set to prevent overfitting during the training process

Figure 2-14. Detailed workflow for training and evaluating a deep learning model

Preventing Overfitting in Deep Neural Networks

Regularization modifies the objective function that we minimize by adding additional terms that penalize large weights. In other words, we change the objective function so that it becomes $Error + \lambda f(\theta)$, where $f(\theta)$ grows larger as the components of $\theta$ grow larger, and $\lambda$ is the regularization strength (another hyperparameter).

The most common type of regularization in machine learning is L2 regularization. It can be implemented by augmenting the error function with the squared magnitude of all weights in the neural network. In other words, for every weight w in the neural network, we add $\frac{1}{2}\lambda w^2$ to the error function. The L2 regularization has the intuitive interpretation of heavily penalizing peaky weight vectors and preferring diffuse weight vectors. This has the appealing property of encouraging the network to use all of its inputs a little rather than using only some of its inputs a lot. Of particular note is that during the gradient descent update, using the L2 regularization ultimately means that every weight is decayed linearly to zero. Because of this phenomenon, L2 regularization is also commonly referred to as weight decay.

Figure 2-15. A visualization of neural networks trained with regularization strengths of 0.01, 0.1, and 1 (in that order)

Another common type of regularization is L1 regularization. Here, we add the term $\lambda |

w | $ for every weight w in the neural network. The L1 regularization has the intriguing property that it leads the weight vectors to become sparse during optimization (i.e., very close to exactly zero). In other words, neurons with L1 regularization end up using only a small subset of their most important inputs and become quite resistant to noise in the inputs. In comparison, weight vectors from L2 regularization are usually diffuse, small numbers. L1 regularization is very useful when you want to understand exactly which features are contributing to a decision. If this level of feature analysis isn’t necessary, we prefer to use L2 regularization because it empirically performs better. |

Max norm constraints enforce an absolute upper bound on the magnitude of the incoming weight vector for every neuron and use projected gradient descent to enforce the constraint. In other words, any time a gradient descent step moves the incoming weight vector such that $\lVert w \rVert^2 > c$, we project the vector back onto the ball (centered at the origin) with radius c.

While training, dropout is implemented by only keeping a neuron active with some probability p (a hyperparameter), or setting it to zero otherwise. Intuitively, this forces the network to be accurate even in the absence of certain information. It prevents the network from becoming too dependent on any one (or any small combination) of neurons. Expressed more mathematically, it prevents overfitting by providing a way of approximately combining exponentially many different neural network architectures efficiently.

Figure 2-16. Dropout sets each neuron in the network as inactive with some random probability during each minibatch of training

Chapter 3. Implementing Neural Networks in TensorFlow

Installing TensorFlow

import tensorflow as tf

deep_learning = tf.constant('Deep Learning')

session = tf.Session()

session.run(deep_learning)

'Deep Learning'

a = tf.constant(2)

b = tf.constant(3)

multiply = tf.multiply(a, b)

session.run(multiply)

6

According to the tensorflow 1.0.0 release notes

tf.mul, tf.sub and tf.neg are deprecated in favor of tf.multiply, tf.subtract and tf.negative.

Creating and Manipulating TensorFlow Variables

# Common tensors from the TensorFlow API docs

tf.zeros(shape, dtype=tf.float32, name=None)

tf.ones(shape, dtype=tf.float32, name=None)

tf.random_normal(shape, mean=0.0, stddev=1.0,

dtype=tf.float32, seed=None,

name=None)

tf.truncated_normal(shape, mean=0.0, stddev=1.0,

dtype=tf.float32, seed=None,

name=None)

tf.random_uniform(shape, minval=0, maxval=None,

dtype=tf.float32, seed=None,

name=None)

When we call tf.Variable, three operations are added to the computation graph:

- The operation producing the tensor we use to initialize our variable

- The

tf.assignoperation, which is responsible for filling the variable with the initializing tensor prior to the variable’s use - The variable operation, which holds the current value of the variable

Figure 3-1. Three operations are added to the graph when instantiating a TensorFlow variable. In this example, we instantiate the variable weights using a random normal initializer.

TensorFlow Operations

Table 3-1. A summary table of TensorFlow operations

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Element-wise mathematical operations | Add, Sub, Mul, Div, Exp, Log, Greater, Less, Equal, … |

| Array operations | Concat, Slice, Split, Constant, Rank, Shape, Shuffle, … |

| Matrix operations | MatMul, MatrixInverse, MatrixDeterminant, … |

| Stateful operations | Variable, Assign, AssignAdd, … |

| Neural network building blocks | SoftMax, Sigmoid, ReLU, Convolution2D, MaxPool, … |

| Checkpointing operations | Save, Restore |

| Queue and synchronization operations | Enqueue, Dequeue, MutexAcquire, MutexRelease, … |

| Control flow operations | Merge, Switch, Enter, Leave, NextIteration |

Placeholder Tensors

A variable is insufficient because it is only meant to be initialized once. Just as variables need to be initialized the first time the computation graph is built, placeholders need to be filled every time the computation graph (or a subgraph) is run.

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, name="x", shape=[None, 784])

W = tf.Variable(tf.random_uniform([784,10], -1, 1), name="W")

multiply = tf.matmul(x, W)

- define a placeholder where x represents a minibatch of data stored as float32’s

- x has 784 columns

- x has an undefined number of rows. This means that x can be initialized with an arbitrary number of data samples

- W demension:784*10, range $\in$ [-1,1]

Sessions in TensorFlow

import tensorflow as tf

from read_data import get_minibatch()

x = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, name="x", shape=[None, 784])

W = tf.Variable(tf.random_uniform([784, 10], -1, 1), name="W")

b = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([10]), name="biases")

output = tf.matmul(x, W) + b

init_op = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess = tf.Session()

sess.run(init_op)

feed_dict = {"x" : get_minibatch()}

sess.run(output, feed_dict=feed_dict)

Figure 3-2. This is a an example of a simple computational graph in TensorFlow

Navigating Variable Scopes and Sharing Variables

def my_network(input):

W_1 = tf.Variable(tf.random_uniform([784, 100], -1, 1), name="W_1")

b_1 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([100]), name="biases_1")

output_1 = tf.matmul(input, W_1) + b_1

W_2 = tf.Variable(tf.random_uniform([100, 50], -1, 1), name="W_2")

b_2 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([50]), name="biases_2")

output_2 = tf.matmul(output_1, W_2) + b_2

W_3 = tf.Variable(tf.random_uniform([50, 10], -1, 1), name="W_3")

b_3 = tf.Variable(tf.zeros([10]), name="biases_3")

output_3 = tf.matmul(output_2, W_3) + b_3

# printing names

print "Printing names of weight parameters"

print W_1.name, W_2.name, W_3.name

print "Printing names of bias parameters"

print b_1.name, b_2.name, b_3.name

return output_3

i_1 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_1")

my_network(i_1)

Printing names of weight parameters

W_1:0 W_2:0 W_3:0

Printing names of bias parameters

biases_1:0 biases_2:0 biases_3:0

<tf.Tensor 'add_2:0' shape=(1000, 10) dtype=float32>

i_2 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_2")

my_network(i_2)

Printing names of weight parameters

W_1_1:0 W_2_1:0 W_3_1:0

Printing names of bias parameters

biases_1_1:0 biases_2_1:0 biases_3_1:0

<tf.Tensor 'add_5:0' shape=(1000, 10) dtype=float32>

TensorFlow’s variable scoping mechanisms are largely controlled by two functions:

tf.get_variable(<name>, <shape>, <initializer>)- Checks if a variable with this name exists, retrieves the variable if it does, or creates it using the shape and initializer if it doesn’t.

tf.variable_scope(<scope_name>)- Manages the namespace and determines the scope in which

tf.get_variableoperates.

- Manages the namespace and determines the scope in which

def layer(input, weight_shape, bias_shape):

weight_init = tf.random_uniform_initializer(minval=-1, maxval=1)

bias_init = tf.constant_initializer(value=0)

W = tf.get_variable("W", weight_shape, initializer=weight_init)

b = tf.get_variable("b", bias_shape, initializer=bias_init)

return tf.matmul(input, W) + b

def my_network(input):

with tf.variable_scope("layer_1"):

output_1 = layer(input, [784, 100], [100])

with tf.variable_scope("layer_2"):

output_2 = layer(output_1, [100, 50], [50])

with tf.variable_scope("layer_3"):

output_3 = layer(output_2, [50, 10], [10])

return output_3

Now let’s try to call my_network twice, just like we did in the preceding code block:

i_1 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_1")

my_network(i_1)

<tf.Tensor 'layer_3/add:0' shape=(1000, 10) dtype=float32>

i_2 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_2")

my_network(i_2)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-8-e22e9d54b2f8> in <module>()

1 i_2 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_2")

----> 2 my_network(i_2)

<ipython-input-6-fd851d0f603b> in my_network(input)

8 def my_network(input):

9 with tf.variable_scope("layer_1"):

---> 10 output_1 = layer(input, [784, 100], [100])

11

12 with tf.variable_scope("layer_2"):

<ipython-input-6-fd851d0f603b> in layer(input, weight_shape, bias_shape)

2 weight_init = tf.random_uniform_initializer(minval=-1, maxval=1)

3 bias_init = tf.constant_initializer(value=0)

----> 4 W = tf.get_variable("W", weight_shape, initializer=weight_init)

5 b = tf.get_variable("b", bias_shape, initializer=bias_init)

6 return tf.matmul(input, W) + b

/Users/zhangjun/anaconda/lib/python2.7/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/variable_scope.pyc in get_variable(name, shape, dtype, initializer, regularizer, trainable, collections, caching_device, partitioner, validate_shape, use_resource, custom_getter)

1047 collections=collections, caching_device=caching_device,

1048 partitioner=partitioner, validate_shape=validate_shape,

-> 1049 use_resource=use_resource, custom_getter=custom_getter)

1050 get_variable_or_local_docstring = (

1051 """%s

/Users/zhangjun/anaconda/lib/python2.7/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/variable_scope.pyc in get_variable(self, var_store, name, shape, dtype, initializer, regularizer, trainable, collections, caching_device, partitioner, validate_shape, use_resource, custom_getter)

946 collections=collections, caching_device=caching_device,

947 partitioner=partitioner, validate_shape=validate_shape,

--> 948 use_resource=use_resource, custom_getter=custom_getter)

949

950 def _get_partitioned_variable(self,

/Users/zhangjun/anaconda/lib/python2.7/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/variable_scope.pyc in get_variable(self, name, shape, dtype, initializer, regularizer, reuse, trainable, collections, caching_device, partitioner, validate_shape, use_resource, custom_getter)

354 reuse=reuse, trainable=trainable, collections=collections,

355 caching_device=caching_device, partitioner=partitioner,

--> 356 validate_shape=validate_shape, use_resource=use_resource)

357

358 def _get_partitioned_variable(

/Users/zhangjun/anaconda/lib/python2.7/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/variable_scope.pyc in _true_getter(name, shape, dtype, initializer, regularizer, reuse, trainable, collections, caching_device, partitioner, validate_shape, use_resource)

339 trainable=trainable, collections=collections,

340 caching_device=caching_device, validate_shape=validate_shape,

--> 341 use_resource=use_resource)

342

343 if custom_getter is not None:

/Users/zhangjun/anaconda/lib/python2.7/site-packages/tensorflow/python/ops/variable_scope.pyc in _get_single_variable(self, name, shape, dtype, initializer, regularizer, partition_info, reuse, trainable, collections, caching_device, validate_shape, use_resource)

651 " Did you mean to set reuse=True in VarScope? "

652 "Originally defined at:\n\n%s" % (

--> 653 name, "".join(traceback.format_list(tb))))

654 found_var = self._vars[name]

655 if not shape.is_compatible_with(found_var.get_shape()):

ValueError: Variable layer_1/W already exists, disallowed. Did you mean to set reuse=True in VarScope? Originally defined at:

File "<ipython-input-6-fd851d0f603b>", line 4, in layer

W = tf.get_variable("W", weight_shape, initializer=weight_init)

File "<ipython-input-6-fd851d0f603b>", line 10, in my_network

output_1 = layer(input, [784, 100], [100])

File "<ipython-input-7-0155c84ecd17>", line 2, in <module>

my_network(i_1)

By default, sharing is not allowed (just to be safe!), but if we want to enable sharing within a variable scope, we can say so explicitly:

with tf.variable_scope("shared_variables") as scope:

i_1 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_1")

my_network(i_1)

scope.reuse_variables()

i_2 = tf.placeholder(tf.float32, [1000, 784], name="i_2")

my_network(i_2)

Managing Models over the CPU and GPU

Supported devices are represented by string IDs and normally consist of the following:

- “/cpu:0”

- The CPU of our machine.

- “/gpu:0”

- The first GPU of our machine, if it has one.

- “/gpu:1”

- The second GPU of our machine, if it has one.

To inspect which devices are used by the computational graph, we can initialize our TensorFlow session with the log_device_placement set to True:

sess = tf.Session(config=tf.ConfigProto(log_device_placement=True))

If we desire to use a specific device, we may do so by using with tf.device to select the appropriate device. If the chosen device is not available, however, an error will be thrown. If we would like TensorFlow to find another available device if the chosen device does not exist, we can pass the allow_soft_placement flag to the session variable as follows:

with tf.device('/gpu:2'):

a = tf.constant([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0], shape=[2, 2], name='a')

b = tf.constant([1.0, 2.0], shape=[2, 1], name='b')

c = tf.matmul(a, b)

sess = tf.Session(config=tf.ConfigProto(

allow_soft_placement=True, log_device_placement=True))

sess.run(c)

The following code is an example of multi-GPU code[fig 3-3]:

c = []

for d in ['/gpu:0', '/gpu:1']:

with tf.device(d):

a = tf.constant([1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0], shape=[2, 2],

name='a')

b = tf.constant([1.0, 2.0], shape=[2, 1], name='b')

c.append(tf.matmul(a, b))

with tf.device('/cpu:0'):

sum = tf.add_n(c)

sess = tf.Session(config=tf.ConfigProto(

log_device_placement=True))

sess.run(sum)

Figure 3-3. Building multi-GPU models in a tower-like fashion

Specifying the Logistic Regression Model in TensorFlow

Our model uses a matrix W representing the weights of the connections in the network, as well as a vector b corresponding to the biases to estimate whether an input x belongs to class i using the softmax expression we talked about earlier:

| $p(y=i | x)=softmax_i(Wx+b)=\frac{e^{W_ix+b_i}}{\sum_j e^{W_jx+b_j}}$ |

Figure 3-4. Interpreting logistic regression as a primitive neural network

We’ll build the the logistic regression model in four phases:

- inference: produces a probability distribution over the output classes given a minibatch

- loss: computes the value of the error function (in this case, the cross-entropy loss)

- training: responsible for computing the gradients of the model’s parameters and updating the model

- evaluate: will determine the effectiveness of a model

def inference(x):

init = tf.constant_initializer(value=0)

W = tf.get_variable("W", [784, 10], initializer=init)

b = tf.get_variable("b", [10], initializer=init)

output = tf.nn.softmax(tf.matmul(x, W) + b)

w_hist = tf.summary.histogram("weights", W)

b_hist = tf.summary.histogram("biases", b)

y_hist = tf.summary.histogram("output", output)

return output

def loss(output, y):

dot_product = y * tf.log(output)

# Reduction along axis 0 collapses each column into a

# single value, whereas reduction along axis 1 collapses

# each row into a single value. In general, reduction along

# axis i collapses the ith dimension of a tensor to size 1.

xentropy = -tf.reduce_sum(dot_product, reduction_indices=1)

loss = tf.reduce_mean(xentropy)

return loss

def training(cost, global_step):

tf.summary.scalar("cost", cost)

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(learning_rate)

train_op = optimizer.minimize(cost, global_step=global_step)

return train_op

def evaluate(output, y):

correct_prediction = tf.equal(tf.argmax(output, 1), tf.argmax(y, 1))

accuracy = tf.reduce_mean(tf.cast(correct_prediction, tf.float32))

tf.summary.scalar("validation error", (1.0 - accuracy))

return accuracy

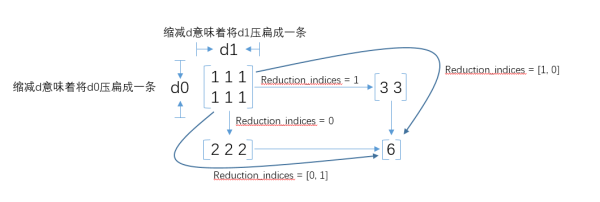

tf.constant_initializer常量初始化函数。tf.reduce_sum求和,由于求和的对象是tensor,所以是沿着tensor的某些维度求和。reduction_indice是指沿tensor的哪些维度求和。

tf.equal是对比这两个矩阵或者向量的相等的元素,如果是相等的那就返回True,反正返回False,返回的值的矩阵维度和A是一样的。- 下面例子代码输出:

[[ True True True False False]]

- 下面例子代码输出:

import tensorflow as tf

import numpy as np

A = [[1,3,4,5,6]]

B = [[1,3,4,3,2]]

with tf.Session() as sess:

print(sess.run(tf.equal(A, B)))

tf.summary.scalarandtf.summary.histogramcommands to log the cost for each minibatch, validation error, and the distribution of parameters

Logging and Training the Logistic Regression Model

import input_data

mnist = input_data.read_data_sets("data/", one_hot=True)

# Parameters

learning_rate = 0.01

training_epochs = 60

batch_size = 100

display_step = 1

with tf.Graph().as_default():

x = tf.placeholder("float", [None, 784]) # mnist data image of shape 28*28=784

y = tf.placeholder("float", [None, 10]) # 0-9 digits recognition => 10 classes

output = inference(x)

cost = loss(output, y)

global_step = tf.Variable(0, name='global_step', trainable=False)

train_op = training(cost, global_step)

eval_op = evaluate(output, y)

summary_op = tf.summary.merge_all()

saver = tf.train.Saver()

sess = tf.Session()

summary_writer = tf.summary.FileWriter("logistic_logs/", graph=sess.graph)

init_op = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess.run(init_op)

# Training cycle

for epoch in range(training_epochs):

avg_cost = 0.

total_batch = int(mnist.train.num_examples/batch_size)

# Loop over all batches

for i in range(total_batch):

minibatch_x, minibatch_y = mnist.train.next_batch(batch_size)

# Fit training using batch data

sess.run(train_op, feed_dict={x: minibatch_x, y: minibatch_y})

# Compute average loss

avg_cost += sess.run(cost, feed_dict={x: minibatch_x, y: minibatch_y})/total_batch

# Display logs per epoch step

if epoch % display_step == 0:

print "Epoch:", '%04d' % (epoch+1), "cost =", "{:.9f}".format(avg_cost)

accuracy = sess.run(eval_op, feed_dict={x: mnist.validation.images, y: mnist.validation.labels})

print "Validation Error:", (1 - accuracy)

summary_str = sess.run(summary_op, feed_dict={x: minibatch_x, y: minibatch_y})

summary_writer.add_summary(summary_str, sess.run(global_step))

saver.save(sess, "logistic_logs/model-checkpoint", global_step=global_step)

print "Optimization Finished!"

accuracy = sess.run(eval_op, feed_dict={x: mnist.test.images, y: mnist.test.labels})

print "Test Accuracy:", accuracy

Extracting data/train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

INFO:tensorflow:Summary name validation error is illegal; using validation_error instead.

Epoch: 0001 cost = 1.174406662

Validation Error: 0.1507999897

Epoch: 0002 cost = 0.661975267

Validation Error: 0.127799987793

Epoch: 0003 cost = 0.550479775

Validation Error: 0.119799971581

Epoch: 0004 cost = 0.496666517

Validation Error: 0.114000022411

Epoch: 0005 cost = 0.463729115

Validation Error: 0.109600007534

Epoch: 0006 cost = 0.440869012

Validation Error: 0.106599986553

Epoch: 0007 cost = 0.423876265

Validation Error: 0.104600012302

Epoch: 0008 cost = 0.410587048

Validation Error: 0.102800011635

Epoch: 0009 cost = 0.399861779

Validation Error: 0.100000023842

Epoch: 0010 cost = 0.390921709

Validation Error: 0.0985999703407

Epoch: 0011 cost = 0.383350472

Validation Error: 0.0975999832153

Epoch: 0012 cost = 0.376742928

Validation Error: 0.0957999825478

Epoch: 0013 cost = 0.370986774

Validation Error: 0.0952000021935

Epoch: 0014 cost = 0.365939115

Validation Error: 0.093800008297

Epoch: 0015 cost = 0.361372554

Validation Error: 0.0917999744415

Epoch: 0016 cost = 0.357271555

Validation Error: 0.090399980545

Epoch: 0017 cost = 0.353570737

Validation Error: 0.0889999866486

Epoch: 0018 cost = 0.350133936

Validation Error: 0.0878000259399

Epoch: 0019 cost = 0.347030580

Validation Error: 0.0888000130653

Epoch: 0020 cost = 0.344142686

Validation Error: 0.0870000123978

Epoch: 0021 cost = 0.341469975

Validation Error: 0.087199985981

Epoch: 0022 cost = 0.338988112

Validation Error: 0.0866000056267

Epoch: 0023 cost = 0.336671517

Validation Error: 0.0860000252724

Epoch: 0024 cost = 0.334482374

Validation Error: 0.0852000117302

Epoch: 0025 cost = 0.332421122

Validation Error: 0.0856000185013

Epoch: 0026 cost = 0.330536905

Validation Error: 0.0856000185013

Epoch: 0027 cost = 0.328713858

Validation Error: 0.0849999785423

Epoch: 0028 cost = 0.327041571

Validation Error: 0.0849999785423

Epoch: 0029 cost = 0.325404955

Validation Error: 0.0845999717712

Epoch: 0030 cost = 0.323815571

Validation Error: 0.0838000178337

Epoch: 0031 cost = 0.322372914

Validation Error: 0.084399998188

Epoch: 0032 cost = 0.320976514

Validation Error: 0.0827999711037

Epoch: 0033 cost = 0.319625769

Validation Error: 0.0838000178337

Epoch: 0034 cost = 0.318344331

Validation Error: 0.0834000110626

Epoch: 0035 cost = 0.317125423

Validation Error: 0.0834000110626

Epoch: 0036 cost = 0.315953904

Validation Error: 0.0825999975204

Epoch: 0037 cost = 0.314849404

Validation Error: 0.0830000042915

Epoch: 0038 cost = 0.313760099

Validation Error: 0.0827999711037

Epoch: 0039 cost = 0.312705152

Validation Error: 0.0820000171661

Epoch: 0040 cost = 0.311696270

Validation Error: 0.0821999907494

Epoch: 0041 cost = 0.310747934

Validation Error: 0.081200003624

Epoch: 0042 cost = 0.309776564

Validation Error: 0.0816000103951

Epoch: 0043 cost = 0.308896091

Validation Error: 0.0802000164986

Epoch: 0044 cost = 0.308059065

Validation Error: 0.0806000232697

Epoch: 0045 cost = 0.307155169

Validation Error: 0.0792000293732

Epoch: 0046 cost = 0.306371177

Validation Error: 0.0795999765396

Epoch: 0047 cost = 0.305602618

Validation Error: 0.0794000029564

Epoch: 0048 cost = 0.304778637

Validation Error: 0.0799999833107

Epoch: 0049 cost = 0.304078800

Validation Error: 0.0788000226021

Epoch: 0050 cost = 0.303349025

Validation Error: 0.0781999826431

Epoch: 0051 cost = 0.302626471

Validation Error: 0.0785999894142

Epoch: 0052 cost = 0.301978953

Validation Error: 0.0781999826431

Epoch: 0053 cost = 0.301298777

Validation Error: 0.0781999826431

Epoch: 0054 cost = 0.300633167

Validation Error: 0.077799975872

Epoch: 0055 cost = 0.300007916

Validation Error: 0.077799975872

Epoch: 0056 cost = 0.299402576

Validation Error: 0.0774000287056

Epoch: 0057 cost = 0.298825037

Validation Error: 0.0776000022888

Epoch: 0058 cost = 0.298242218

Validation Error: 0.0771999955177

Epoch: 0059 cost = 0.297690147

Validation Error: 0.0771999955177

Epoch: 0060 cost = 0.297135488

Validation Error: 0.0781999826431

Optimization Finished!

Test Accuracy: 0.9194

Every epoch, we run the tf.summary.merge_all in order to collect all summary statistics we’ve logged and use a tf.summary.FileWriter to write the log to disk.

Leveraging TensorBoard to Visualize Computation Graphs and Learning

TensorFlow comes with a visualization tool called TensorBoard, which provides an easy-to-use interface for navigating through our summary statistics.

!tensorboard --logdir=logistic_logs

Starting TensorBoard b'39' on port 6006

(You can navigate to http://192.168.199.139:6006)

WARNING:tensorflow:Found more than one graph event per run, or there was a metagraph containing a graph_def, as well as one or more graph events. Overwriting the graph with the newest event.

WARNING:tensorflow:Found more than one graph event per run, or there was a metagraph containing a graph_def, as well as one or more graph events. Overwriting the graph with the newest event.

WARNING:tensorflow:Found more than one metagraph event per run. Overwriting the metagraph with the newest event.

^CTraceback (most recent call last):

File "/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/bin/tensorboard", line 11, in <module>

sys.exit(main())

File "/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/lib/python3.5/site-packages/tensorflow/tensorboard/tensorboard.py", line 151, in main

tb_server.serve_forever()

File "/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/lib/python3.5/socketserver.py", line 232, in serve_forever

ready = selector.select(poll_interval)

File "/Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.5/lib/python3.5/selectors.py", line 376, in select

fd_event_list = self._poll.poll(timeout)

KeyboardInterrupt

As shown in Figure 3-5, the first tab contains information on the scalar summaries that we collected.

Figure 3-5. The TensorBoard events view

And as Figure 3-6 shows, there’s also a tab that allows us to visualize the full computation graph that we’ve built.

Figure 3-6. The TensorBoard graph view

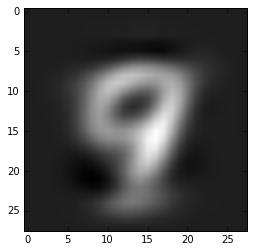

Building a Multilayer Model for MNIST in TensorFlow

We construct a feed-forward model with two hidden layers, each with 256 ReLU neurons, as shown in Figure 3-7.

Figure 3-7. A feed-forward network powered by ReLU neurons with two hidden layers

The performance of deep neural networks very much depends on an effective initialization of its parameters. For example, changing tf.random_normal_initializer back to the tf.random_uniform_initializer we used in the logistic regression example significantly hurts performance.

def layer(input, weight_shape, bias_shape):

weight_init = tf.random_normal_initializer(stddev=(2.0/weight_shape[0])**0.5)

bias_init = tf.constant_initializer(value=0)

W = tf.get_variable("W", weight_shape, initializer=weight_init)

b = tf.get_variable("b", bias_shape, initializer=bias_init)

return tf.nn.relu(tf.matmul(input, W) + b)

def inference(x):

with tf.variable_scope("hidden_1"):

hidden_1 = layer(x, [784, n_hidden_1], [n_hidden_1])

with tf.variable_scope("hidden_2"):

hidden_2 = layer(hidden_1, [n_hidden_1, n_hidden_2], [n_hidden_2])

with tf.variable_scope("output"):

output = layer(hidden_2, [n_hidden_2, 10], [10])

return output

def loss(output, y):

xentropy = tf.nn.softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(logits=output, labels=y)

loss = tf.reduce_mean(xentropy)

return loss

def training(cost, global_step):

tf.summary.scalar("cost", cost)

optimizer = tf.train.GradientDescentOptimizer(learning_rate)

train_op = optimizer.minimize(cost, global_step=global_step)

return train_op

def evaluate(output, y):

correct_prediction = tf.equal(tf.argmax(output, 1), tf.argmax(y, 1))

accuracy = tf.reduce_mean(tf.cast(correct_prediction, tf.float32))

tf.summary.scalar("validation error", (1.0 - accuracy))

return accuracy

关于 tf.nn.softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits

We perform the softmax while computing the loss instead of during the inference phase of the network.

tf.nn.softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(logits, labels, name=None):

- 第一个参数logits:就是神经网络最后一层的输出,如果有batch的话,它的大小就是[batchsize,num_classes],单样本的话,大小就是num_classes

- 第二个参数labels:实际的标签,大小同上

具体的执行流程大概分为两步:

- 先对网络最后一层的输出做一个softmax($softmax(x)_i=\frac{exp(x_i)}{\sum_j exp(x_j)}$),这一步通常是求取输出属于某一类的概率,对于单样本而言,输出就是一个num_classes大小的向量($[Y_1,Y_2,Y_3\cdots]$其中$Y_1,Y_2,Y_3\cdots$分别代表了是属于该类的概率)

- softmax的输出向量$[Y_1,Y_2,Y_3\cdots]$和样本的实际标签做一个交叉熵,公式如下:

$H_{y’}(y)=-\sum_i y_i’ log(y_i)$

- 其中$y_i’$指代实际的标签中第i个的值(用mnist数据举例,如果是3,那么标签是[0,0,0,1,0,0,0,0,0,0],除了第4个值为1,其他全为0)

- $y_i$就是softmax的输出向量$[Y_1,Y_2,Y_3\cdots]$中,第i个元素的值

- 显而易见,预测越准确,结果的值越小(别忘了前面还有负号),最后求一个平均,得到我们想要的loss

实例代码:

import tensorflow as tf

#our NN's output

logits=tf.constant([[1.0,2.0,3.0],[1.0,2.0,3.0],[1.0,2.0,3.0]])

#step1:do softmax

y=tf.nn.softmax(logits)

#true label

y_=tf.constant([[0.0,0.0,1.0],[0.0,0.0,1.0],[0.0,0.0,1.0]])

#step2:do cross_entropy

cross_entropy = -tf.reduce_sum(y_*tf.log(y))

#do cross_entropy just one step

cross_entropy2=tf.reduce_sum(tf.nn.softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits(logits=logits, labels=y_))#dont forget tf.reduce_sum()!!

with tf.Session() as sess:

softmax=sess.run(y)

c_e = sess.run(cross_entropy)

c_e2 = sess.run(cross_entropy2)

print("step1:softmax result=")

print(softmax)

print("step2:cross_entropy result=")

print(c_e)

print("Function(softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits) result=")

print(c_e2)

输出结果是:

step1:softmax result=

[[ 0.09003057 0.24472848 0.66524094]

[ 0.09003057 0.24472848 0.66524094]

[ 0.09003057 0.24472848 0.66524094]]

step2:cross_entropy result=

1.22282

Function(softmax_cross_entropy_with_logits) result=

1.2228

import input_data

mnist = input_data.read_data_sets("data/", one_hot=True)

import tensorflow as tf

# Architecture

n_hidden_1 = 256

n_hidden_2 = 256

# Parameters

learning_rate = 0.01

training_epochs = 60

batch_size = 100

display_step = 1

with tf.Graph().as_default():

with tf.variable_scope("mlp_model"):

x = tf.placeholder("float", [None, 784]) # mnist data image of shape 28*28=784

y = tf.placeholder("float", [None, 10]) # 0-9 digits recognition => 10 classes

output = inference(x)

cost = loss(output, y)

global_step = tf.Variable(0, name='global_step', trainable=False)

train_op = training(cost, global_step)

eval_op = evaluate(output, y)

summary_op = tf.summary.merge_all()

saver = tf.train.Saver()

sess = tf.Session()

summary_writer = tf.summary.FileWriter("mlp_logs/", graph=sess.graph)

init_op = tf.global_variables_initializer()

sess.run(init_op)

# saver.restore(sess, "mlp_logs/model-checkpoint-66000")

# Training cycle

for epoch in range(training_epochs):

avg_cost = 0.

total_batch = int(mnist.train.num_examples/batch_size)

# Loop over all batches

for i in range(total_batch):

minibatch_x, minibatch_y = mnist.train.next_batch(batch_size)

# Fit training using batch data

sess.run(train_op, feed_dict={x: minibatch_x, y: minibatch_y})

# Compute average loss

avg_cost += sess.run(cost, feed_dict={x: minibatch_x, y: minibatch_y})/total_batch

# Display logs per epoch step

if epoch % display_step == 0:

print "Epoch:", '%04d' % (epoch+1), "cost =", "{:.9f}".format(avg_cost)

accuracy = sess.run(eval_op, feed_dict={x: mnist.validation.images, y: mnist.validation.labels})

print "Validation Error:", (1 - accuracy)

summary_str = sess.run(summary_op, feed_dict={x: minibatch_x, y: minibatch_y})

summary_writer.add_summary(summary_str, sess.run(global_step))

saver.save(sess, "mlp_logs/model-checkpoint", global_step=global_step)

print "Optimization Finished!"

accuracy = sess.run(eval_op, feed_dict={x: mnist.test.images, y: mnist.test.labels})

print "Test Accuracy:", accuracy

Extracting data/train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

INFO:tensorflow:Summary name validation error is illegal; using validation_error instead.

Epoch: 0001 cost = 1.167901315

Validation Error: 0.193799972534

Epoch: 0002 cost = 0.583657532

Validation Error: 0.0952000021935

Epoch: 0003 cost = 0.337281553

Validation Error: 0.0824000239372

Epoch: 0004 cost = 0.291787940

Validation Error: 0.0753999948502

Epoch: 0005 cost = 0.264843191

Validation Error: 0.0681999921799

Epoch: 0006 cost = 0.244155136

Validation Error: 0.063000023365

Epoch: 0007 cost = 0.227775839

Validation Error: 0.0587999820709

Epoch: 0008 cost = 0.213482748

Validation Error: 0.0572000145912

Epoch: 0009 cost = 0.201193266

Validation Error: 0.0537999868393

Epoch: 0010 cost = 0.190703814

Validation Error: 0.0526000261307

Epoch: 0011 cost = 0.180840817

Validation Error: 0.0483999848366

Epoch: 0012 cost = 0.172169948

Validation Error: 0.0468000173569

Epoch: 0013 cost = 0.164293182

Validation Error: 0.0429999828339

Epoch: 0014 cost = 0.157237688

Validation Error: 0.0422000288963

Epoch: 0015 cost = 0.150315270

Validation Error: 0.0404000282288

Epoch: 0016 cost = 0.143809539

Validation Error: 0.0397999882698

Epoch: 0017 cost = 0.138288142

Validation Error: 0.0383999943733

Epoch: 0018 cost = 0.132807644

Validation Error: 0.0368000268936

Epoch: 0019 cost = 0.127695854

Validation Error: 0.0360000133514

Epoch: 0020 cost = 0.123071070

Validation Error: 0.0360000133514

Epoch: 0021 cost = 0.118457685

Validation Error: 0.0333999991417

Epoch: 0022 cost = 0.114368538

Validation Error: 0.035000026226

Epoch: 0023 cost = 0.110391890

Validation Error: 0.0335999727249

Epoch: 0024 cost = 0.106810061

Validation Error: 0.0329999923706

Epoch: 0025 cost = 0.103084836

Validation Error: 0.0314000248909

Epoch: 0026 cost = 0.099609090

Validation Error: 0.0317999720573

Epoch: 0027 cost = 0.096475270

Validation Error: 0.0314000248909

Epoch: 0028 cost = 0.093608136

Validation Error: 0.0310000181198

Epoch: 0029 cost = 0.090823234

Validation Error: 0.0302000045776

Epoch: 0030 cost = 0.087971685

Validation Error: 0.0310000181198

Epoch: 0031 cost = 0.085327522

Validation Error: 0.0284000039101

Epoch: 0032 cost = 0.083025288

Validation Error: 0.0293999910355

Epoch: 0033 cost = 0.080345904

Validation Error: 0.0278000235558

Epoch: 0034 cost = 0.078043377

Validation Error: 0.0275999903679

Epoch: 0035 cost = 0.076065099

Validation Error: 0.0266000032425

Epoch: 0036 cost = 0.073843680

Validation Error: 0.0270000100136

Epoch: 0037 cost = 0.071988347

Validation Error: 0.0271999835968

Epoch: 0038 cost = 0.069911680

Validation Error: 0.0261999964714

Epoch: 0039 cost = 0.068045618

Validation Error: 0.0253999829292

Epoch: 0040 cost = 0.066214094

Validation Error: 0.0260000228882

Epoch: 0041 cost = 0.064684716

Validation Error: 0.0253999829292

Epoch: 0042 cost = 0.062954863

Validation Error: 0.0253999829292

Epoch: 0043 cost = 0.061380908

Validation Error: 0.025200009346

Epoch: 0044 cost = 0.059666186

Validation Error: 0.0257999897003

Epoch: 0045 cost = 0.058348657

Validation Error: 0.0248000025749

Epoch: 0046 cost = 0.056857154

Validation Error: 0.0253999829292

Epoch: 0047 cost = 0.055460378

Validation Error: 0.0246000289917

Epoch: 0048 cost = 0.054099406

Validation Error: 0.0246000289917

Epoch: 0049 cost = 0.052707463

Validation Error: 0.0246000289917

Epoch: 0050 cost = 0.051495020

Validation Error: 0.0243999958038

Epoch: 0051 cost = 0.050231972

Validation Error: 0.0243999958038

Epoch: 0052 cost = 0.049027650

Validation Error: 0.0249999761581

Epoch: 0053 cost = 0.048119295

Validation Error: 0.0238000154495

Epoch: 0054 cost = 0.046903143

Validation Error: 0.0238000154495

Epoch: 0055 cost = 0.045721100

Validation Error: 0.0234000086784

Epoch: 0056 cost = 0.044620886

Validation Error: 0.0235999822617

Epoch: 0057 cost = 0.043739291

Validation Error: 0.022400021553

Epoch: 0058 cost = 0.042631193

Validation Error: 0.022400021553

Epoch: 0059 cost = 0.041887093

Validation Error: 0.0231999754906

Epoch: 0060 cost = 0.040904860

Validation Error: 0.022400021553

Optimization Finished!

Test Accuracy: 0.9744

Chapter 4. Beyond Gradient Descent

Local Minima in the Error Surfaces of Deep Networks

The primary challenge in optimizing deep learning models is that we are forced to use minimal local information to infer the global structure of the error surface. This is a hard problem because there is usually very little correspondence between local and global structure.

In Chapter 2, we talked about how a mini-batch version of gradient descent can help navigate a troublesome error surface when there are spurious regions of magnitude zero gradients. But as we can see in Figure 4-1, even a stochastic error surface won’t save us from a deep local minimum.

Figure 4-1. Mini-batch gradient descent may aid in escaping shallow local minima, but often fails when dealing with deep local minima, as shown

How Pesky Are Spurious Local Minima in Deep Networks?

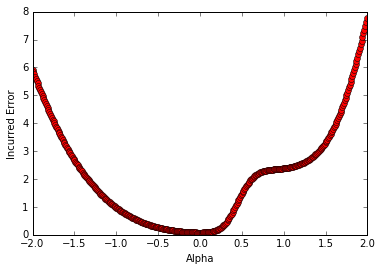

Goodfellow et al.:Instead of analyzing the error function over time, they cleverly investigated what happens on the error surface between a randomly initialized parameter vector and a successful final solution by using linear interpolation. So given a randomly initialized parameter vector $\theta_i$ and stochastic gradient descent (SGD) solution $\theta_f$, we aim to compute the error function at every point along the linear interpolation $\theta_\alpha=\alpha \cdot \theta_f + (1-\alpha) \cdot \theta_i$

In other words, they wanted to investigate whether local minima would hinder our gradient-based search method even if we knew which direction to move in. They showed that for a wide variety of practical networks with different types of neurons, the direct path between a randomly initialized point in the parameter space and a stochastic gradient descent solution isn’t plagued with troublesome local minima.

We can even demonstrate this ourselves using the feed-foward ReLU network we built in Chapter 3.

- Using a checkpoint file that we saved while training our original feed-forward network, we can re-instantiate the inference and loss components while also maintaining a list of pointers to the variables in the original graph for future use in.

var_list_opt(where opt stands for the optimal parameter settings) - Similarly, we can reuse the component constructors to create a randomly initialized network. Here we store the variables in

var_list_randfor the next step of our program. - With these two networks appropriately initialized, we can now construct the linear interpolation using the mixing parameters

alphaandbeta.

%matplotlib inline

import input_data

mnist = input_data.read_data_sets("data/", one_hot=True)

import tensorflow as tf

import numpy as np

from multilayer_perceptron import inference, loss

sess = tf.Session()

x = tf.placeholder("float", [None, 784]) # mnist data image of shape 28*28=784

y = tf.placeholder("float", [None, 10]) # 0-9 digits recognition => 10 classes

with tf.variable_scope("mlp_model") as scope:

output_opt = inference(x)

cost_opt = loss(output_opt, y)

saver = tf.train.Saver()

scope.reuse_variables()

var_list_opt = ["hidden_1/W", "hidden_1/b", "hidden_2/W", "hidden_2/b", "output/W", "output/b"]

var_list_opt = [tf.get_variable(v) for v in var_list_opt]

saver.restore(sess, "mlp_logs/model-checkpoint-33000")

with tf.variable_scope("mlp_init") as scope:

output_rand = inference(x)

cost_rand = loss(output_rand, y)

scope.reuse_variables()

var_list_rand = ["hidden_1/W", "hidden_1/b", "hidden_2/W", "hidden_2/b", "output/W", "output/b"]

var_list_rand = [tf.get_variable(v) for v in var_list_rand]

init_op = tf.variables_initializer(var_list_rand)

sess.run(init_op)

feed_dict = {

x: mnist.test.images,

y: mnist.test.labels,

}

print sess.run([cost_opt, cost_rand], feed_dict=feed_dict)

with tf.variable_scope("mlp_inter") as scope:

alpha = tf.placeholder("float", [1, 1])

h1_W_inter = var_list_opt[0] * (1 - alpha) + var_list_rand[0] * (alpha)

h1_b_inter = var_list_opt[1] * (1 - alpha) + var_list_rand[1] * (alpha)

h2_W_inter = var_list_opt[2] * (1 - alpha) + var_list_rand[2] * (alpha)

h2_b_inter = var_list_opt[3] * (1 - alpha) + var_list_rand[3] * (alpha)

o_W_inter = var_list_opt[4] * (1 - alpha) + var_list_rand[4] * (alpha)

o_b_inter = var_list_opt[5] * (1 - alpha) + var_list_rand[5] * (alpha)

h1_inter = tf.nn.relu(tf.matmul(x, h1_W_inter) + h1_b_inter)

h2_inter = tf.nn.relu(tf.matmul(h1_inter, h2_W_inter) + h2_b_inter)

o_inter = tf.nn.relu(tf.matmul(h2_inter, o_W_inter) + o_b_inter)

cost_inter = loss(o_inter, y)

tf.summary.scalar("interpolated_cost", cost_inter)

Extracting data/train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

INFO:tensorflow:Restoring parameters from mlp_logs/model-checkpoint-33000

[0.080450691, 2.382179]

We can vary the value of alpha to understand how the error surface changes as we traverse the line between the randomly initialized point and the final SGD solution:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

summary_writer = tf.summary.FileWriter("linear_interp_logs/", graph=sess.graph)

summary_op = tf.summary.merge_all()

results = []

for a in np.arange(-2, 2, 0.01):

feed_dict = {

x: mnist.test.images,

y: mnist.test.labels,

alpha: [[a]],

}

cost, summary_str = sess.run([cost_inter, summary_op], feed_dict=feed_dict)

summary_writer.add_summary(summary_str, (a + 2)/0.01)

results.append(cost)

plt.plot(np.arange(-2, 2, 0.01), results, 'ro')

plt.ylabel('Incurred Error')

plt.xlabel('Alpha')

plt.show()

The cost function of a three-layer feed-forward network as we linearly interpolate on the line connecting a randomly initialized parameter vector and an SGD solution

Flat Regions in the Error Surface

More generally, given an arbitrary function, a point at which the gradient is the zero vector is called a critical point.

For a one-dimensional cost function, a critical point can take one of three forms, as shown in Figure 4-4.

Figure 4-4. Analyzing a critical point along a single dimension

This means given a random critical point in a random one-dimensional function, it has one-third probability of being a local minimum. This means that if we have a total of k critical points, we can expect to have a total of $\frac{k}{3}$ local minima.

We can also extend this to higher dimensional functions. Consider a cost function operating in a d-dimensional space.

Figure 4-5. A saddle point over a two-dimensional error surface

In general, in a d-dimensional parameter space, we can slice through a critical point on d different axes. A critical point can only be a local minimum if it appears as a local minimum in every single one of the d one-dimensional subspaces. Using the fact that a critical point can come in one of three different flavors(local minima,local maxima and saddle points) in a one-dimensional subspace, we realize that the probability that a random critical point is in a random function is $\frac{1}{3^d}$. This means that a random function function with k critical points has an expected number of $\frac{k}{3^d}$ local minima. In other words, as the dimensionality of our parameter space increases, local minima become exponentially more rare.

It seems like these flat segments of the error surface are pesky but ultimately don’t prevent stochastic gradient descent from converging to a good answer. However, it does pose serious problems for methods that attempt to directly solve for a point where the gradient is zero.

When the Gradient Points in the Wrong Direction

As an example, we consider an error surface defined over a two-dimensional parameter space, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Figure 4-6. Local information encoded by the gradient usually does not corroborate the global structure of the error surface

Specifically, we realize that only when the contours are perfectly circular does the gradient always point in the direction of the local minimum. However, if the contours are extremely elliptical (as is usually the case for the error surfaces of deep networks), the gradient can be as inaccurate as 90 degrees away from the correct direction!

The general problem with taking a significant step in this direction, however, is that the gradient could be changing under our feet as we move! We demonstrate this simple fact in Figure 4-7. Going back to the two-dimensional example, if our contours are perfectly circular and we take a big step in the direction of the steepest descent, the gradient doesn’t change direction as we move. However, this is not the case for highly elliptical contours.

Figure 4-7. We show how the direction of the gradient changes as we move along the direction of steepest descent (as determined from a starting point). The gradient vectors are normalized to identical length to emphasize the change in direction of the gradient vector.

More generally, we can quantify how the gradient changes under our feet as we move in a certain direction by computing second derivatives. Specifically, we want to measure $\frac{\partial(\partial E / \partial w_j)}{\partial w_j}$, which tells us how the gradient component for $w_j$ changes as we change the value of $w_i$. We can compile this information into a special matrix known as the Hessian matrix (H). And when describing an error surface where the gradient changes underneath our feet as we move in the direction of steepest descent, this matrix is said to be ill-conditioned.

We can now use a second-order approximation via Taylor series:

$E(x) \approx E(x^{(i)}) + (x-x^{(i)})^T g + \frac{1}{2} (x-x^{(i)})^T H (x-x^{(i)})$

If we go further to state that we will be moving $\epsilon$ units in the direction of the gradient, we can further simplify our expression:

$E(x^{(i)} - \epsilon g) \approx E(x^{(i)}) - \epsilon g^T g + \frac{1}{2}\epsilon^2 g^THg$

This expression consists of three terms:

- the value of the error function at the original parameter vector,

- the improvement in error afforded by the magnitude of the gradient,

- a correction term that incorporates the curvature of the surface as represented by the Hessian matrix.

Momentum-Based Optimization

Fundamentally, the problem of an ill-conditioned Hessian matrix manifests itself in the form of gradients that fluctuate wildly. As a result, one popular mechanism for dealing with ill-conditioning bypasses the computation of the Hessian, and instead, focuses on how to cancel out these fluctuations over the duration of training.

Our goal, then, is to somehow generate an analog for velocity in our optimization algorithm. We can do this by keeping track of an exponentially weighted decay of past gradients. The premise is simple: every update is computed by combining the update in the last iteration with the current gradient. Concretely, we compute the change in the parameter vector as follows:

$v_i = mv_{i-1} - \epsilon g_i$

$\theta_i = \theta_{i-1} + v_i$

In other words, we use the momentum hyperparameter m to determine what fraction of the previous velocity to retain in the new update, and add this “memory” of past gradients to our current gradient. This approach is commonly referred to as momentum.

To better visualize how momentum works, we’ll explore a toy example. Specifically, we’ll investigate how momentum affects updates during a random walk. A random walk is a succession of randomly chosen steps. In our example, we’ll imagine a particle on a line that, at every time interval, randomly picks a step size between -10 and 10 and takes a moves in that direction. This is simply expressed as:

step_range = 10

step_choices = range(-1 * step_range, step_range + 1)

rand_walk = [random.choice(step_choices) for x in xrange(100)]

We’ll then simulate what happens when we use a slight modification of momentum (i.e., the standard exponentially weighted moving average algorithm) to smooth our choice of step at every time interval. Again, we can concisely express this as:

momentum_rand_walk = [random.choice(step_choices)]

for i in xrange(len(rand_walk) - 1):

prev = momentum_rand_walk[-1]

rand_choice = random.choice(step_choices)

new_step = momentum * prev + (1 - momentum) * rand_choice

momentum_rand_walk.append()

Figure 4-8. Momentum smooths volatility in the step sizes during a random walk using an exponentially weighted moving average

The resulting speedup is staggering. We display how the cost function changes over time by comparing the TensorBoard visualizations in Figure 4-9. The figure demonstrates that to achieve a cost of 0.1 without momentum (right) requires nearly 18,000 steps (minibatches), whereas with momentum (left), we require just over 2,000.

Figure 4-9. Comparing training a feed-forward network with (right) and without (left) momentum demonstrates a massive decrease in training time

A Brief View of Second-Order Methods

Several second-order methods, however, have been researched over the past several years that attempt to approximate the Hessian directly.

Conjugate Gradient Descent

In steepest descent, we compute the direction of the gradient and then line search to find the minimum along that direction. We jump to the minimum and then recompute the gradient to determine the direction of the next line search. It turns out that this method ends up zigzagging a significant amount, as shown in Figure 4-9, because each time we move in the direction of steepest descent, we undo a little bit of progress in another direction. A remedy to this problem is moving in a conjugate direction relative to the previous choice instead of the direction of steepest descent. The conjugate direction is chosen by using an indirect approximation of the Hessian to linearly combine the gradient and our previous direction. With a slight modification, this method generalizes to the nonconvex error surfaces we find in deep networks.

Figure 4-10. The method of steepest descent often zigzags; conjugate descent attempts to remedy this issue

Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (BFGS)

BFGS algorithm attempts to compute the inverse of the Hessian matrix iteratively and use the inverse Hessian to more effectively optimize the parameter vector. A more memory-efficient version known as L-BFGS.

Learning Rate Adaptation

AdaGrad—Accumulating Historical Gradients

This learning rate is inversely scaled with respect to the square root of the sum of the squares (root mean square) of all the parameter’s historical gradients.

Flat regions may force AdaGrad to decrease the learning rate before it reaches a minimum.

$r_i=r_{i-1} + g_i \odot g_i$

- $r_0=0$

- $\odot$ is element-wise tensor multiplication

- $g_i \odot g_i$ the square of all the gradient parameters

$\theta_i = \theta_{i-1} - \frac{\epsilon}{\sigma \oplus \sqrt{r_i}} \odot g$

- $\epsilon$ global learning rate, is divided by the square root of the gradient accumulation vector

- $\sigma(\approx 10^{-7})$ ,a tiny number in order to prevent division by zero

In TensorFlow, a built-in optimizer allows for easily utilizing AdaGrad as a learning algorithm:

tf.train.AdagradOptimizer(learning_rate,

initial_accumulator_value=0.1,

use_locking=False,

name='Adagrad')

- the $\epsilon$ and initial gradient accumulation vector are rolled together into the

initial_accumulator_valueargument

RMSProp—Exponentially Weighted Moving Average of Gradients

$r_i=\rho r_{i-1} + (1 - \rho) g_i \odot g_i$

- $\rho$ the decay factor determines how long we keep old gradients

tf.train.RMSPropOptimizer(learning_rate, decay=0.9,

momentum=0.0, epsilon=1e-10,

use_locking=False, name='RMSProp')

- Unlike in Adagrad, we pass in $\delta$ separately as the epsilon argument to the constructor.

Adam—Combining Momentum and RMSProp

$\tilde{m_i} = \frac{m_i}{1-\beta_1^i}$

$v_i=\frac{v_i}{1-\beta_2^i}$

$\theta_i=\theta_{i-1} - \frac{\epsilon}{\sigma \oplus \sqrt{v_i}\tilde{m_i}}$

tf.train.AdamOptimizer(learning_rate=0.001, beta1=0.9,

beta2=0.999, epsilon=1e-08,

use_locking=False, name='Adam')

Optimization Algorithms Experiment

!python optimzer_mlp.py sgd

Extracting data/train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

sgd

2017-08-15 08:28:09.183430: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use SSE4.1 instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 08:28:09.183453: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use SSE4.2 instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 08:28:09.183459: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use AVX instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 08:28:09.183464: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use AVX2 instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 08:28:09.183469: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use FMA instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

Epoch: 0001 cost = 1.023527871

Validation Error: 0.119799971581

Epoch: 0101 cost = 0.018873566

Validation Error: 0.019200026989

Epoch: 0201 cost = 0.005179930

Validation Error: 0.0184000134468

Epoch: 0301 cost = 0.002607897

Validation Error: 0.0171999931335

Epoch: 0401 cost = 0.001667035

Validation Error: 0.0166000127792

Optimization Finished!

Test Accuracy: 0.9807

!python optimzer_mlp.py momentum

Extracting data/train-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/train-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-images-idx3-ubyte.gz

Extracting data/t10k-labels-idx1-ubyte.gz

momentum

2017-08-15 09:07:09.048477: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use SSE4.1 instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 09:07:09.048500: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use SSE4.2 instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 09:07:09.048506: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use AVX instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 09:07:09.048511: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use AVX2 instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

2017-08-15 09:07:09.048515: W tensorflow/core/platform/cpu_feature_guard.cc:45] The TensorFlow library wasn't compiled to use FMA instructions, but these are available on your machine and could speed up CPU computations.

Epoch: 0001 cost = 0.919267848

Validation Error: 0.270600020885

Epoch: 0101 cost = 0.260265864

Validation Error: 0.128000020981

Epoch: 0201 cost = 0.260049450

Validation Error: 0.127799987793

Epoch: 0301 cost = 0.260005093

Validation Error: 0.128199994564

Epoch: 0401 cost = 0.259985650

Validation Error: 0.127799987793

Optimization Finished!

Test Accuracy: 0.8683

Chapter 5. Convolutional Neural Networks

Vanilla Deep Neural Networks Don’t Scale

In MNIST, our images were only 28 x 28 pixels and were black and white. As a result, a neuron in a fully connected hidden layer would have 784 incoming weights. This seems pretty tractable for the MNIST task, and our vanilla neural net performed quite well. This technique, however, does not scale well as our images grow larger. For example, for a full-color 200 x 200 pixel image, our input layer would have 200 x 200 x 3 =120,000 weights.

Figure 5-3. The density of connections between layers increases intractably as the size of the image increases

As we’ll see, the neurons in a convolutional layer are only connected to a small, local region of the preceding layer. A convolutional layer’s function can be expressed simply: it processes a three-dimensional volume of information to produce a new three-dimensional volume of information.

Figure 5-4. Convolutional layers arrange neurons in three dimensions, so layers have width, height, and depth

Filters and Feature Maps

A filter is essentially a feature detector.

Figure 5-5. We’ll analyze this simple black-and-white image as a toy example

Let’s say that we want to detect vertical and horizontal lines in the image. For example, to detect vertical lines, we would use the feature detector on the top, slide it across the entirety of the image, and at every step check if we have a match. This result is our feature map, and it indicates where we’ve found the feature we’re looking for in the original image. We can do the same for the horizontal line detector (bottom), resulting in the feature map in the bottom-right corner.

Figure 5-6. Applying filters that detect vertical and horizontal lines on our toy example

This operation is called a convolution. We take a filter and we multiply it over the entire area of an input image.

Filters represent combinations of connections (one such combination is highlighted in Figure 5-7) that get replicated across the entirety of the input.

The output layer is the feature map generated by this filter. A neuron in the feature map is activated if the filter contributing to its activity detected an appropriate feature at the corresponding position in the previous layer.

Figure 5-7. Representing filters and feature maps as neurons in a convolutional layer

Express the feature map as follows:

$m_{ij}^k=f((W \cdot x)_{ij} + b^k)$

- the $k^{th}$ feature map in layer m as $m^k$

- the corresponding filter by the values of its weights upper W

- assuming the neurons in the feature map have bias $b^k$ (note that the bias is kept identical for all of the neurons in a feature map)

And we have accumulated three feature maps, one for eyes, one for noses, and one for mouths. We know that a particular location contains a face if the corresponding locations in the primitive feature maps contain the appropriate features (two eyes, a nose, and a mouth). In other words, to make decisions about the existence of a face, we must combine evidence over multiple feature maps.

As a result, feature maps must be able to operate over volumes, not just areas. This is shown below in Figure 5-8. Each cell in the input volume is a neuron. A local portion is multiplied with a filter (corresponding to weights in the convolutional layer) to produce a neuron in a filter map in the following volumetric layer of neurons.

Figure 5-8. Representing a full-color RGB image as a volume and applying a volumetric convolutional filter

The depth of the output volume of a convolutional layer is equivalent to the number of filters in that layer, because each filter produces its own slice. We visualize these relationships in Figure 5-9.

Figure 5-9. A three-dimensional visualization of a convolutional layer, where each filter corresponds to a slice in the resulting output volume

Full Description of the Convolutional Layer

This input volume has the following characteristics:

- Its width $w_{in}$

- Its height $h_{in}$

- Its depth $d_{in}$

- Its zero padding p

This volume is processed by a total of k filters, which represent the weights and connections in the convolutional network. These filters have a number of hyperparameters, which are described as follows:

- Their spatial extent e, which is equal to the filter’s height and width.

- Their stride s, or the distance between consecutive applications of the filter on the input volume. If we use a stride of 1, we get the full convolution described in the previous section. We illustrate this in Figure 5-10.

- The bias b (a parameter learned like the values in the filter) which is added to each component of the convolution.

Figure 5-10. An illustration of a filter’s stride hyperparameter

This results in an output volume with the following characteristics:

- Its function f, which is applied to the incoming logit of each neuron in the output volume to determine its final value

- Its width $w_{out}=\lceil \frac{w_{in}-e+2p}{s} \rceil + 1$

- Its height $h_{out}=\lceil \frac{h_{in}-e+2p}{s} \rceil + 1$

- Its depth $d_{out}=k$

Figure 5-11. This is a convolutional layer with an input volume that has width 5, height 5, depth 3, and zero padding 1. There are 2 filters, with spatial extent 3 and applied with a stride of 2. It results in an output volume with width 3, height 3, and depth 2. We apply the first convolutional filter to the upper-leftmost 3 x 3 piece of the input volume to generate the upper-leftmost entry of the first depth slice.

Figure 5-12. Using the same setup as Figure 5-11, we generate the next value in the first depth slice of the output volume.

TensorFlow provides us with a convenient operation to easily perform a convolution on a minibatch of input volumes (note that we must apply our choice of function ourselves and it is not performed by the operation itself):

tf.nn.conv2d(input, filter, strides, padding, use_cudnn_on_gpu=True, name=None)

input:a four-dimensional tensor of size $N \times h_{in} \times w_{in} \times d_{in}$, where is the number of examples in our minibatch.filter:also a four-dimensional tensor representing all of the filters applied in the convolution. It is of size $e \times e \times d_{in} \times k$.- The resulting tensor emitted by this operation has the same structure as